How fracking could unlock a clean energy future, fueling a new type of carbon-free power plant

Southern California Edison, one of the country’s largest power companies, has just announced a deal to buy electricity from a seven-year-old start-up called Fervo Energy. Like other energy companies, Fervo will use hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” to tap an energy source trapped deep underground.

But instead of oil and gas, Fervo is hunting heat, a more abundant resource that neither pollutes the air nor contributes to global warming. The heat will fuel a new type of power plant: an enhanced geothermal plant.

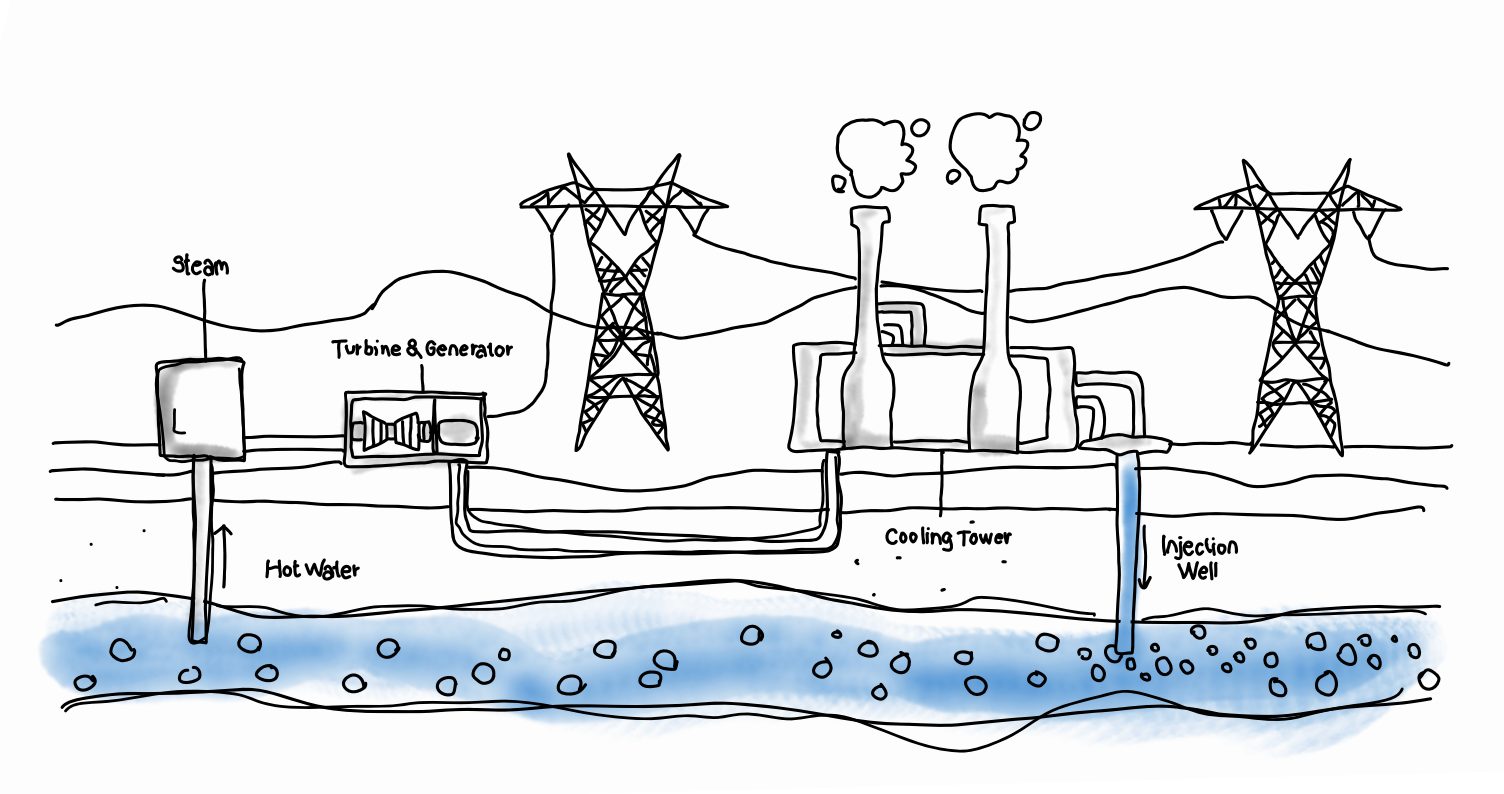

Most power plants work by converting a turbine’s rotating energy into electricity. Many of the world’s energy challenges stem from this seemingly simple problem: how to get a turbine to keep spinning.

Coal power plants, for example, burn coal to boil water and pump steam through the turbine. They make reliable electricity, but they also emit pollution and greenhouse gases that cause global warming.

In contrast, conventional geothermal power plants capture steam from natural underground hot springs in places such as Iceland or the Geysers in Northern California. These require a rare combination of geologic conditions — heat, underground water and porous rock.

Enhanced geothermal plants use technology pioneered by oil and gas drillers to reproduce the conditions of a conventional geothermal well. This makes it possible to extract heat in many more places.

When completed in 2028, the new enhanced geothermal plant will add 400 megawatts of carbon-free electricity to the power grid (Southern California Edison has agreed to buy 320 megawatts; the rest will go to smaller power providers.)

That is less than one-fifth of the generating capacity of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant, which by itself provides nearly a tenth of California’s electricity. But as the first power purchasing agreement between an electric utility and an enhanced geothermal company, the deal represents a milestone in the effort to limit global warming.

“It’s a big deal,” said Fervo founder and CEO Tim Latimer. “It shows the important role that geothermal is going to play on the grid as a 24/7 carbon-free energy resource.”

What’s at stake

- Geothermal plants can run all day, every day.

Models foresee solar panels and wind turbines playing a large role in the carbon-free power grid of the future. But when the wind fails to blow or the sun is hidden, utility companies will need more reliable clean power sources. If they cannot add nuclear power plants and hydroelectric dams, they can turn to enhanced geothermal.

- Enhanced geothermal has huge potential.

Conventional geothermal plants, like the Geysers in California, generate just 0.4 percent of U.S. electricity. Enhanced geothermal resources, which face fewer geological constraints, are more than 100 times bigger than naturally occurring resources, according to an Energy Department analysis. The Energy Department also estimates that there are 300,000 workers who already know how to frack and run power plants who could find jobs in the enhanced geothermal industry.

- Electricity is just the beginning.

Enhanced geothermal can help cut emissions from other activities that produce three times the greenhouse gas emissions of electricity generation. Researchers are learning to extract lithium — a key component in electric vehicle batteries — from the fluid that comes out of the ground. Geothermal wells can also be used for heating, another major source of emissions.

Fracking supporters have long touted its supposed environmental benefits. George P. Mitchell, the Texas oilman who, in the 1980s and ’90s, sank more than a billion dollars into figuring out how to make fracking profitable, believed it would unlock so much natural gas that power plants would no longer need to run on coal, which releases about twice as much carbon dioxide.

It worked — and made Mitchell a billionaire in the process. Between 2005 and 2021, cheaper natural gas replaced so much coal that it drove a larger reduction in U.S. CO2 emissions than replacing coal with emissions-free electricity sources such as wind and solar.

Yet the natural gas unleashed by Mitchell’s fracking revolution was never a perfect solution. Burning natural gas still emits greenhouse gases, making it incompatible with the United States’ and other countries’ climate goals. Plus, some scientists now say that so much methane leaks during fracking that natural gas warms the planet as much as coal does.

Fracking for heat releases no greenhouse gases. But to meaningfully contribute to emissions cuts, enhanced geothermal will need to expand quickly.

Developers say they are hamstrung by a needlessly long permitting process, which takes years to complete. Lawmakers in both houses of Congress have introduced bipartisan bills that would make it as easy to drill for heat as for oil and gas.

Enhanced geothermal’s biggest constraint is how much heat can be found underground. The hottest rock is out West, according to a recent government assessment, but cooler rock formations could fuel power plants in Texas, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and at least a dozen other states.

Where geologic conditions are favorable for enhanced geothermal

Note: Favorability data is available for the contiguous United States. Areas are shaded from lighter to darker, indicating the least to most favorable conditions. Regions shown in white were not hot enough to be assessed for geothermal potential.

To extract enough heat in places with cooler rock, geothermal developers must drill 15,000 feet or deeper, which is more expensive. Faster drilling helped the oil and gas industry dig deeper to squeeze more profits out of shale rock, and analysts expect geothermal drilling speed to similarly improve.

Still, investors may be unwilling to fund geothermal exploration in cooler, untested rock, according to a recent Energy Department analysis. Government-funded demonstration projects could ease investors’ concerns by proving enhanced geothermal’s potential in new places.

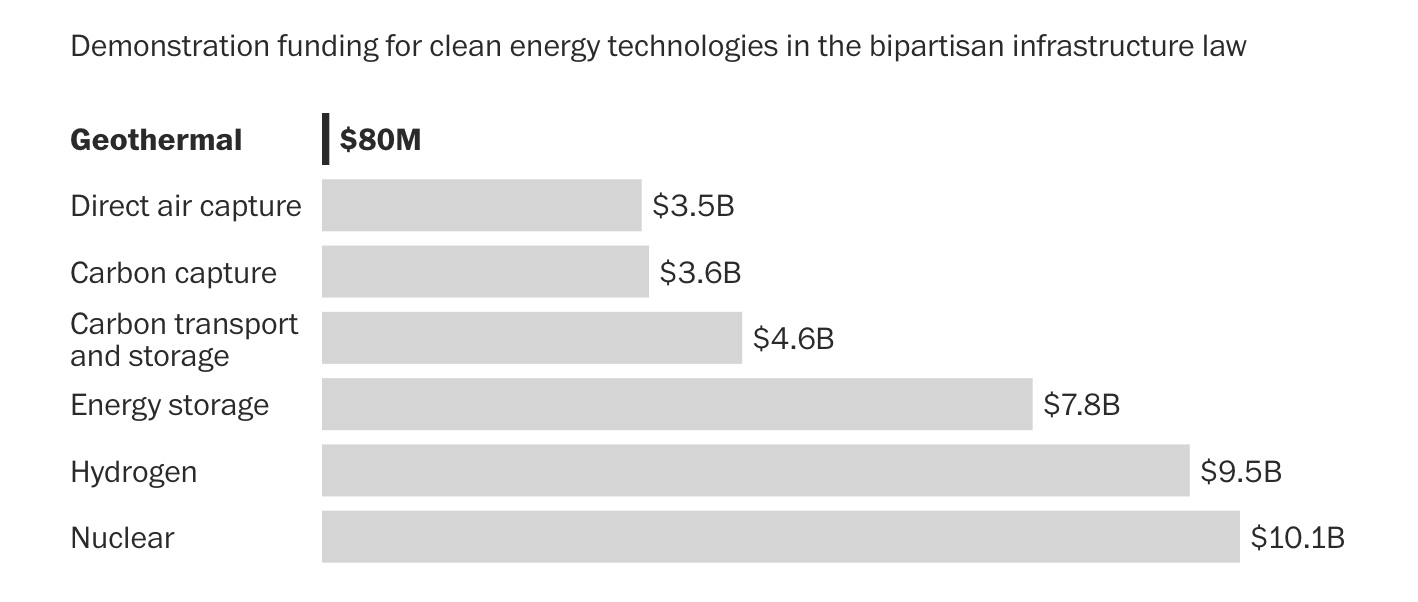

Funding 10 demonstration projects would cost $4.5 billion, the Energy Department analysis estimated. That amount would put enhanced geothermal on par with other clean energy technologies that received funding for demonstration projects in 2021’s bipartisan infrastructure law.

“I certainly think geothermal is deserving of more resources than it was awarded thus far,” said Michelle Solomon, a senior policy analyst at the Energy Innovation think tank, which supports enhanced geothermal.

Even in the West, where the rock is known to be hot, a government-funded demonstration project helped pave the way for Fervo’s wells. That project, known as FORGE, began in 2015 and did not generate power until 2022.

“I do not believe that any of the advances that have happened right now, with commercial liftoff of this technology, would have happened without federal dollars,” said Lauren Boyd, the director of the Energy Department’s Geothermal Technologies Office, who managed the FORGE project.

Boyd has worked for 16 years to make enhanced geothermal a commercially viable energy technology. Now, all the pieces are clicking into place. Fracking for heat has been proved to work, and the urgency of climate change is forcing energy companies and governments to look for new ways to make clean, reliable power.

“It’s really incredible to see this happen,” Boyd said.

Check my work

- I based my illustration of how enhanced geothermal works on the Energy Department’s Next-Generation Geothermal Power liftoff report. The figures on test funding for different clean energy technologies were also from that report and provided to me by the DOE. Those figures are available in this computational notebook.

The data for the map of geothermal resource availability comes from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Preliminary Monthly Electric Generator Inventory. The map data is available in this computational notebook.

You can use the code and data to produce your own analyses and charts — and to make sure mine are accurate. To get in touch, email me and my editor, Monica Ulmanu.

This story originally appeared in The Washington Post's Climate Lab column on July 18, 2024.

The Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation funded a landmark study, “The Future of Geothermal in Texas: The Coming Century of Growth & Prosperity in the Lone Star State,” released on January 24, 2023. The report represents a multi-year, multi-disciplinary, cross-collaborative effort by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin, Southern Methodist University, Rice University, Texas A&M University, the University of Houston, University Lands, and the International Energy Agency. For more information on the study, click here.

NEWS

Hide Full Index

Show Full Index

View All News