George Mitchell's foundation challenges industry orthodoxy

WASHINGTON - Four years ago, a group of oil and gas executives and environmental experts, assembled by the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation, prepared to publish a report calling on Texas regulators to adopt rules to reduce the risk of water contamination from oil and gas production — in response to numerous complaints by residents living close to drilling sites.

But the oil executives, after working on the study for three years, started getting cold feet about having their companies’ names attached to those findings. The report was put on hold, never to be published, said Marilu Hastings, vice president of sustainability programs at the foundation.

“It was the usual suspects,” she said, declining to name the executives or their companies. “On the day before publication, led by one company in particular, they said they would not put their names and dropped out. It was probably the plan from the beginning.”

Founded by George Mitchell — the man often often dubbed the “father of fracking” — the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation has used the family’s oil fortune to promote environmental causes for decades. But six years after Mitchell’s death, the Austin-based foundation has evolved into an unlikely critic of the oil and gas industry, as the shale boom sweeps the United States.

Run by the Mitchells’ children and grandchildren, the foundation has become one of the nation’s leading patrons of research into the public health and the environmental effects of hydraulic fracturing, as well as a passionate advocate for the tightening of government regulations over drilling — the very thing U.S. oil and gas companies lobbied against for years.

The campaign was initiated by Mitchell himself, who at the last board meeting before his death implored his family to work to force companies to drill more responsibly, according to notes from the meeting.

“All the environmental complaints everyone was making about fracking, he felt strongly they were totally unnecessary, and you could do this right,” said Katherine Lorenz, Mitchell’s granddaughter and president of the Mitchell Foundation. “He believed the problems are due to negligence, and he was outspoken on the greater need for regulation. He said that over and over to me.”

For more than a decade, U.S. oil and gas companies have fought claims of flammable water and methane leaks that contribute to climate change, maintaining that the hydraulic fracturing boom has proceeded without long-term damage to land and water — save a few isolated incidents by less reputable firms. But as the family of one of the industry’s legends turns on them, it has made for an awkward situation.

Asked about the foundation’s call for more regulations on oil and gas drilling, Todd Staples, president of the Texas Oil and Gas Association, declined an interview and sent a statement praising Mitchell’s “pioneering work.” He added, “All sectors of oil and natural gas are heavily regulated and the industry continues to be a leader in developing solutions that are advancing environmental progress.”

Steve Everly, a consultant and spokesman for the industry group Texans for Natural Gas, questioned the notion that more research on fracking was needed while downplaying any conflict between the foundation’s work and industry.

“This isn’t Earthworks or the Sierra Club saying ban natural gas,” he said. “George was a little more progressive than others may have been. Different companies and executives have different views.”

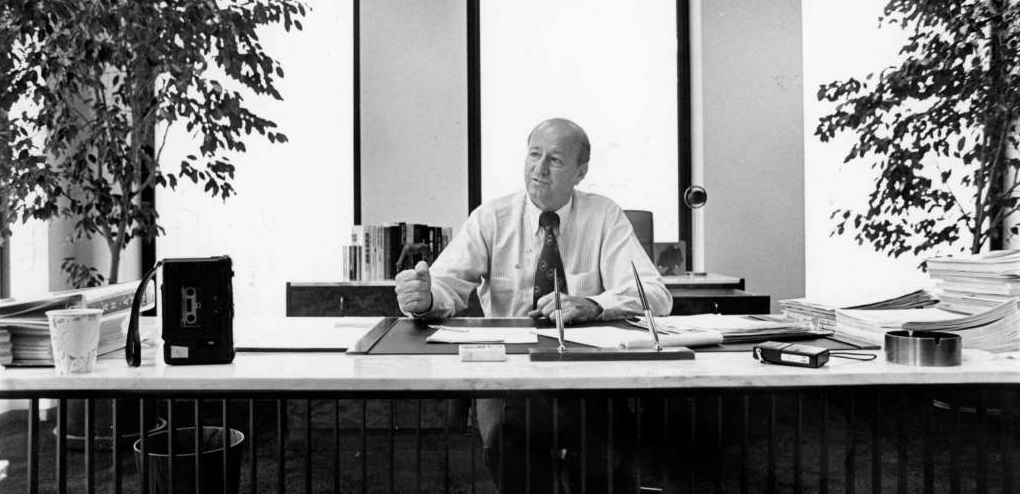

Unusual oil man

Long before he revolutionized the technology of cracking open shale rocks with a high-pressure mixture of water, sand and chemicals to unlock trapped natural gas deposits, Mitchell was not known as your typical Texas oil man. Swept up in the budding environmentalism of the 1960s, he regaled family with ideas gleamed from books such as Buckminster Fuller’s “Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth,” which warned the earth had finite resources. which, if not properly maintained, would mean its end.

Mitchell then took his budding oil fortune and developed 27,000 acres of timberland north of Houston into a nature-centric model community complete with wildlife preserves, a concert pavilion and walking trails - naming it The Woodlands.

Of fracking, which netted him $3.1 billion when he sold his company in 2001 to the Oklahoma exploration and production firm Devon Energy, he was not shy about expressing his concerns.

“Mostly, it’s the loud voices at the extremes who are dominating the debate: those who want either no fracking or no additional regulation of it,” Mitchell wrote in an op-ed with then New York mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2012. “As usual, the voices in the sensible center are getting drowned out — with serious repercussions for our country’s future.”

His descendants now are carrying that mantle. With a $300 million in assets, the Mitchell foundation is funding everything from a campaign to grow rooftop solar systems in Texas to a gala honoring the longtime fracking critic Tom “Smitty” Smith, the former director of the activist group Public Citizen Texas.

At an event in Washington last month, the Aspen Institute released a report sponsored by the Mitchell Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, warning that “while many of the documented impacts associated with oil and gas development have been manageable to date, research is still thin, and effective governance practices have not been sufficiently baked into practice on a broad scale.”

“They’re one of the biggest environmental funders in the state, funding a lot of really important work,” said Luke Metzger, executive director of the non-profit Environment Texas. “Though I should disclose we’re a recipient of their grant money.”

Nowhere is the foundation’s work bringing them into greater conflict with the oil and gas industry than West Texas, where the drilling boom is spreading beyond the well-established oil towns Midland and Odessa.

Worried about the intrusion of rigs, supply trucks and worker camps into the countries surrounding Big Bend National Park, the Mitchell Foundation launched the Respect Big Bend Coalition earlier this year. The aim is to bring together land owners, environmental groups and even oil companies to minimize the impact on an iconic desert landscape.

Middle ground

“Big Bend is one of the most bio diverse regions in western hemisphere,” said Hastings, the foundation’s sustainability director. “Yes, there’s no drilling [near the park] right now. People ask why are you spending your time preparing. All you have to do is drive down the street to the Eagle Ford and see what’s going to happen. If you go in after the fact, it’s too late.”

More than 40 years after its founding, the Mitchell Foundation has developed a reputation for its ability to work with the oil industry in ways that other environmentalists cannot. When the foundation went looking for partners earlier this year for a project at Rice University to speed the development of carbon capture technology, it succeeded bring together interests as diverse as Occidental Petroleum, Dow Chemical and the Environmental Defense Fund.

Joe Kiesecker, a scientist with The Nature Conservancy, a national conservation group whose work in West Texas is funded by the Mitchell Foundation, said the affiliation with the foundation helped his work with oil companies including BP and Royal Dutch Shell in developing climate change policy.

“If I were to knock on a door with energy regulatory folks or developers,” Kiesecker said, “I might knock for a lot longer if I’m just the Nature Conservancy.”

In part, that’s a product of the foundation’s namesake. In addition, the foundation doesn’t argue against fracking altogether, maintaining that it benefits the U.S. economy and simply needs to be done more responsibly.

But as climate scientists’ warnings of environmental catastrophe grow increasingly dire, the Mitchell family’s outlook is changing, too. Lorenz, Mitchell’s 40-year-old granddaughter who previously ran a nonprofit helping farmers in Mexico grow organic crops, said she believed the world would eventually need to move away from natural gas. She admits it was not something her grandfather said in his lifetime, explaining the consequences of climate change were not as clear while he was still active in the foundation.

“This is not the case where we feel bad how the money was made,”she said. “Our values, using science to inform everything we do, is a direct, direct piece of the legacy coming from him.”

This story also appeared on the front page of the Houston Chronicle's business section on Sunday, November 3, 2019.

NEWS

Hide Full Index

Show Full Index

View All News