A Missing Component in the One Water Conversation

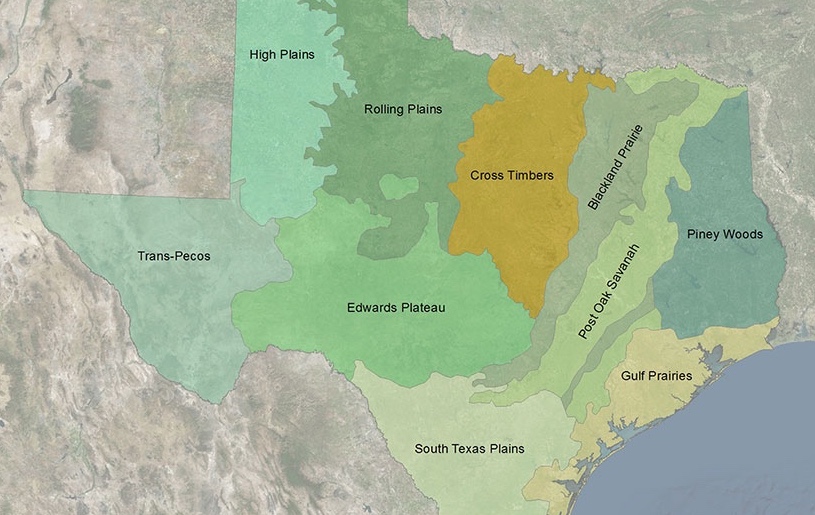

To many Texans, the vast limestone savannah of the Edwards Plateau is an area that one must cross while traveling to Big Bend, Marfa, and other points west. Yet hidden beneath this sea of grasses and trees is the key to one of Texas’s most precious resources, the origin of the state’s iconic Central Texas rivers.

The San Saba, Llano, Guadalupe, Medina, Sabinal, Frio, Nueces, and Devils rivers all originate from springs flowing from canyon walls cut into the sides of the Edwards Plateau. Some of the precipitation falling on the Plateau finds its way into cracks, crevices, and conduits in the limestone, emerging much later and many miles away as springflow that maintains the flow of these rivers in which we love and depend upon.

Unfortunately, this elaborate and somewhat mysterious plumbing system—to date, we only have been unable to figure out what drop of rainfall goes to what specific spring—has a limiting factor: drought.

Through analysis of the volume of water into and out of the Edwards Plateau system, researchers have learned that during periods that receive 70 percent or less of annual average precipitation (e.g., 14 inches versus 20 inches), the amount of recharge (water that finds its way into cracks and crevices) approaches zero. During these dry years, there is more water evaporating into the atmosphere and little left to soak into the ground and, eventually, replenish these springs that are so critical to life.

The good news: there are management practices that rural landowners can take action on to offset the effects of drought on springflow and streamflows. And, these practices need to be included in the One Water discussion.

To date, most of the conversations about One Water have focused on integrating the use of urban water flows—stormwater, rainwater, wastewater—into a single system. What is missing from the discussions of this innovative approach is how management of the contributing watershed (those lands that drain to an urban water supply intake) can also improve our water loss resistance.

The Llano River is a major tributary to the Highland Lakes, the water supply for the City of Austin and other Central Texas communities which are experiencing exponential population growth.

The Llano River Field Station at Texas Tech University at Junction recently collaborated with local stakeholders to develop the Upper Llano River Watershed Protection Plan (WPP). This holistic plan addresses water quality and quantity shortcomings through a variety of management strategies, including control of feral hogs and axis deer, streambank and riparian restoration, control of invasive species, prescribed burning, and brush control.

In creating the Upper Llano River WPP, stakeholders used an ecological model developed at Texas Tech to simulate changes in water quality and availability resulting from the implementation of management recommendations in the WPP. Of particular interest to this discussion are the results from simulating the removal of Ashe-juniper or cedar from selected locations in the Upper Llano.

Due to its dense canopy, only about 20 percent of precipitation that falls over Ashe-juniper infiltrates into the ground, whereas infiltration rates associated with native grasses are greater than 80 percent. WPP model results suggest that over the course of 25 years, removing 9,000 acres of brush annually, coupled with follow up prescribed burning, decreases evapotranspiration by 63,000 to 75,000 acre-feet annually during normal years and about 46,000 acre feet annually during drier periods. However, the positive hydrologic response—increased water availability resulting from decreased evapotranspiration—has a lag time of approximately 11 years following brush control.

How much water is 75,000 acre-feet annually? That volume equates to just over 100 cubic feet per second (cfs). For comparison, the mean flow of the Llano River at Junction is about 190 cfs.

While it is unlikely that there is a 1:1 relationship between decreases in evapotranspiration and corresponding increases in recharge and baseflow, the potential hydrologic benefits associated with improved brush control and other upriver land stewardship practices in contributing watersheds from the Edwards Plateau (or any contributing watershed for that matter) certainly should be a part of any One Water discussion.

The future of our landscape across Texas is in jeopardy as population growth and climate change stretch our precious water resources thin and complicates water management during our famous weather extremes.

Across the state, many community leaders, water planners, and policymakers are wrestling with how to best manage water as to maximize economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems. Leaders in sustainable solutions are rethinking water management practices, working to advance more resilient strategies. Let’s make sure One Water—both within urban and rural environments—helps inform our path forward.

Tyson Broad is the Watershed Coordinator for the Llano River Field Station at Texas Tech University at Junction, overseeing the implementation of the Upper Llano River Watershed Protection Plan, a 10-year stakeholder-driven strategy for maintaining healthy ecological conditions in the watershed. In 2008, Tyson co-founded the Llano River Watershed Alliance, a landowner and stakeholder group committed to protecting and enhancing the watershed through collaboration, education, and community participation. Tyson also worked nine years for the U.S. Geological Survey in Portland, Oregon. He has a B.S. in Geography from Texas A&M University and an M.S. in Geography from Oregon State University. Tyson may be contacted at tyson.broad@ttu.edu.

Editor's note: The views expressed by contributors to the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation's blogging initiative, "Advancing the state of Water, Texas with a One Water approach" are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the foundation. The foundation works as an engine of change in both policy and practice, supporting high-impact projects at the nexus of environmental protection, social equity, and economic vibrancy. Follow the Mitchell Foundation on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up for regular updates from the foundation.

Hide Full Index

Show Full Index

View All Blog Posts