One Water: The Future of Land and Water in Central Texas

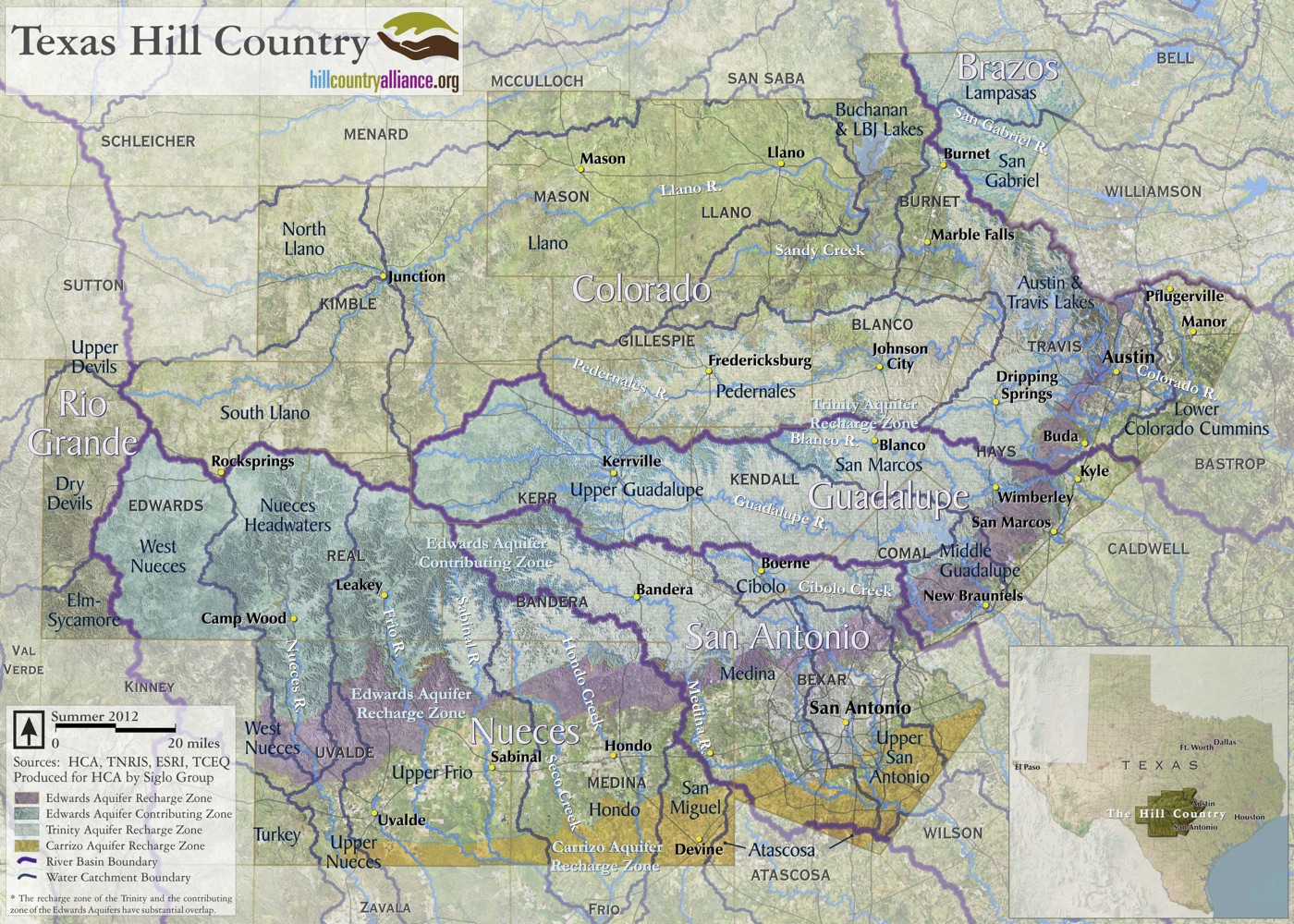

For centuries, the Texas Hill Country has been a region defined by its water resources. Early European settlers traced the paths of the San Antonio, Nueces, Guadalupe, and Colorado Rivers, following their rocky beds, spring-fed tributaries, and shallow draws, no doubt noting every seep and spring along the way.

Before the Europeans, numerous tribes of indigenous peoples hunted, gathered, and fished along these same creeks and rivers. Evidence of their preference for the rivers and the spring sites of the Hill Country is easy to read in the archeology of burned rock middens, ancient campsites, and remnant arrowheads.

Livelihoods in the early days of European settlement of the Hill Country were built and lost on the fortunes of wet years and dry. Every good rancher knew the carrying capacity of their land and how to manage livestock levels to maintain soil moisture.

Not a drop was wasted. It’s easy to appreciate the value of water when you have to carry it, one bucket at a time, from the well, spring, creek, or river out back.

Today’s water story in the Texas Hill Country, however, is much different. Would our forefathers recognize our relationship with water today? In as little as four or five generations—since the era of our grandmothers’ mothers and grandmothers—we have lost that deep and abiding connection to water—where it originates—and its value to our lives.

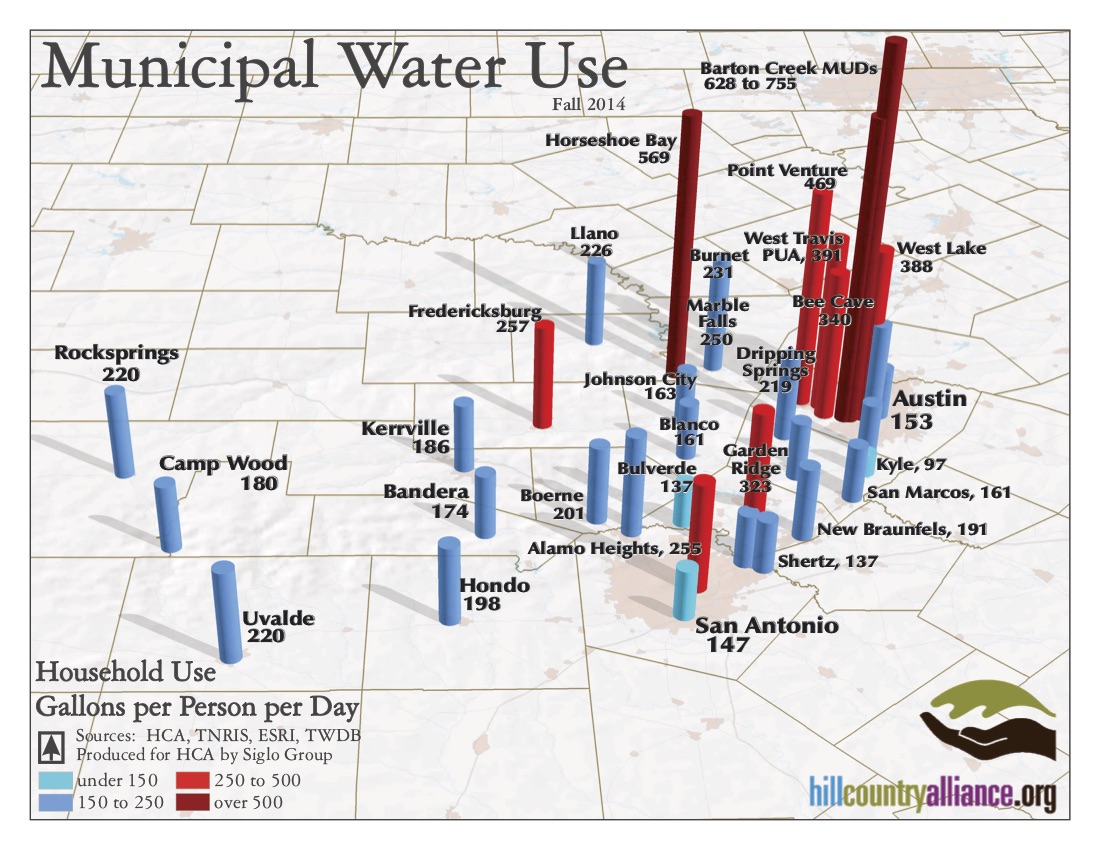

The advent of well drilling technology and major pipeline infrastructure has opened otherwise water-constrained areas for development. We now dump upwards of a third of our clean, treated municipal drinking water onto our lawns, golf courses, and gardens statewide, and closer to 50 percent in some communities.

Over-pumping from limited Hill Country aquifers threatens the spring flow that sustains our most iconic rivers and swimming holes. In Hays County, two landowner-developers are seeking permits to pump a combined 1.2 billion gallons per year from the Trinity Aquifer. We know that this part of the aquifer provides flow to the San Marcos River, the Blanco River, tributary creeks, Jacob’s Well, and thousands of private water wells. The Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District estimates that the level of pumping requested may completely de-water the Cow Creek (Middle Trinity) Aquifer within seven years—the very same water on which many Hays County residents depend as their sole source.

We also see growing threats to the water quality in our Hill Country creeks. Booming development yields increased impervious cover and additional runoff. More and more often, developers are seeking permits to dump treated wastewater effluent into dry or ephemeral creeks. While some Hill Country rivers can handle the nutrient loading from treated wastewater discharge (and many Texas rivers depend on it for their baseflow), many of our pristine creeks with little or low flow simply cannot manage the treated wastewater input. Often this results in algal blooms, nutrient loading that destroys the natural aquatic food chain, and diminishes water quality making our waterways unswimmable, undrinkable, and off-limits for human contact.

More than 1,500 miles of Hill Country Creeks, rivers and streams are listed as impaired.

As we look to add three to five million additional residents to the 17 counties of the Hill Country by 2050, how will we ensure water quantity and quality to sustain the homes, businesses, and quality of life that defines this region of Texas?

THE SOLUTION IS A MINDSET CHANGE

One Water is a term that refers to the holistic approach to water management, although it's nothing new when we consider the history of our predecessor’s relationship to water resources.

It simply means considering all water—whether groundwater, surface water, rainfall, stormwater, drinking water, wastewater, or even new sources such as air conditioning condensate—as part of the complete water balance. One Water poses the question, “How can we more holistically manage these resources for the benefit of humans, the environment, the economy, and our quality of life?” It is the kind of question that we at the Hill Country Alliance ask every day.

The beauty of One Water is that it finds solutions not only by looking at our demand for water but, importantly, by generating new supplies of water.

Stormwater is no longer a nuisance to be shunted away through concrete culverts as quickly as possible—it is something to be stored in rainwater gardens, bioswales, and cisterns. Air conditioning condensate and grey water can be used to flush toilets and to keep gardens lush in times of drought. By switching to distributed infrastructure models, we can put water collection, treatment, and wastewater treatment closer to the source of where it is generated and used.

The adoption of a One Water approach will take the work of more than just nonprofits like the Hill Country Alliance. Most importantly, it will require citizens and community members to demand a long-term approach to water planning. It will demand innovation from engineering firms, builders, and designers exploring more nonconventional solutions. It will take the work (and vision) of city policymakers and water utility managers to invest in infrastructure changes that will have long-term payouts.

RURAL AND URBAN PARTNERSHIPS

Ultimately, the future of the rapidly urbanizing communities of the Hill Country—including three of the top 10 fastest growing counties in the nation—will depend on the continued stewardship of the rural residents of the area.

The vast majority of the water we drink, swim in and enjoy all along the central IH35 corridor begins as rainfall on the lands of the Hill Country. The stewards of those rural lands—the ranchers, farmers, and landowners—are doing their part to ensure long-term water supplies for Austin and San Antonio. A new landowner coalition in the Hill Country has formed to learn more about the drivers of spring flow and aquifer health in order to keep Hill Country creeks full of water, even in times of drought. We would all do well to pay attention to their findings and seek opportunities to support those stewardship efforts whenever we can.

In the same vein, the future of our rural Hill Country will depend on the quick adoption of a One Water approach within the rapidly developing urban core. Let’s ask developers to bring forward-thinking ideas to the table on how they’ll ensure responsible water management for new construction. Let’s demand our cities take a more nuanced approach to water management. Let’s look to our state legislature to see how we can remove barriers to innovation in water management.

Water is THE sustaining element behind the beauty, quality of life, and economic vitality of the Hill Country. One Water is the best way to ensure the continued prosperity of our region for future generations.

Katherine Romans is the executive director of the Hill Country Alliance, a nonprofit focused on protecting the water, land, communities and night skies of the Texas Hill Country. She has more than a decade of nonprofit and legislative experience in natural resource issues, and has been working on issues of growth and conservation with the Hill Country Alliance for five years. Katherine holds a Master of Environmental Management from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

Editor's note: The views expressed by contributors to the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation's blogging initiative, "Advancing the state of Water, Texas with a One Water approach" are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the foundation. The foundation works as an engine of change in both policy and practice, supporting high-impact projects at the nexus of environmental protection, social equity, and economic vibrancy. Follow the Mitchell Foundation on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up for regular updates from the foundation.

Hide Full Index

Show Full Index

View All Blog Posts